Dear Reader; Supporter of Mine and Spiritual Patron of Every Gay to Ever Yell About a Film,

I’m sorry that this newsletter, a platform for me to write literally whatever I want, and to make as much or as little sense as I feel so moved, has taken such a long time to land in your inbox. In truth, it’s not that I had a lack of films or television or even gay moments to pull from. I have a list of approximately 100 movies, and a sublist of at least a dozen milves with homoerotic filmographies (your time will come, Susan Sarandon). It’s just that I didn’t want to write, and moreover, I didn’t really know how.

Shortly after my last newsletter, so fantastically penned by Phoenix Casino, I began this essay. However, at that time I also received a PTSD diagnosis, got myself into what I thought was intensive clinical treatment that would fix me as a person, and promptly fell into a very, very ill-fitting therapeutic relationship. It disrupted my work, my sense of self, my personal relationships, and it very rudely questioned my identity as a queer person. In short, it fucking sucked and I’m overwhelmed by the fact that I had to work so hard to quit something that I thought was going to help me.

But fuck it, I did quit, and picking this newsletter back up (aided in part by bribing myself to type with a new, obnoxiously clackety mechanical keyboard) feels like a huge victory.

I know that this may not be the most fun personal insight to read. It is not very fun to share, as I imagine this e-mail appearing in your notifications, prompting an expectation of good clean lesbian cinephilia. Surprise! I’m depressed AND I’m a dyke film freak. You know what that means, right? No, not my “it was just OK” takedown of Portrait of a Lady on Fire. I’m not that self-immolating.

In order to soft launch my way back into this passion project, and your hearts, I’m sending you into 2022 with an indulgent dispatch on two subjects near and dear and ruinous to my heart: lesbian cowboys and loneliness. Thank you for sticking with me. May next year be a better one.

____________________________________________________________

One of the most purposefully romanticized images of loneliness we have on film is that of the American cowboy. Often traipsing through artificially desolate, uninhabited landscapes that tower over him, all he has is his horse, his bedroll that he stashes with a rotating cast of devoted homesteading girls, and his gun. And maybe he has a begrudgingly-shouldered mission to rescue or capture a maiden or a missing husband from the “evil” group of Native or Mexican characters who have mysteriously disappeared from the land they cared for, only to reappear from behind a cactus.

But in any case, the cowboy doesn’t want all this fuss. He wants to tip his hat to his dainty benefactor, and ride off toward the sunset. He revels in his lonesome love: the drought for miles and the sky above.

Maybe you’re tired of thinking about loneliness. I wouldn’t blame you. The absurd weight of the loneliness I’ve felt over the past year and a half was so crushing that my brain reset itself to convince me that I wasn’t actually abnormally lonely at all, because loneliness was how I’ve always moved through the world. I even cried about it in yet another essay on gay film, this time the odes to joy and lust and isolation from Jenni Olson.

For me, deconstructing the filmic image of the solo cowboy is so appealing because it’s a model for self-imposed suffering. The architecture of the cowboy’s backdrop is an awe-inspiring, perfect vehicle for imagined emotional strength and physical endurance. But believing in this perpetual image of lonely cool is very closely in-line with reading an interview with a new artist or filmmaker who rebuffs the conformist capitalism of Big Hollywood, and then finding out their uncle is Steven Spielberg. There’s no obstacle for you! You just made that shit up!

As a tragicomic aside, John Wayne, the most iconic Hollywood cowboy bar none, wasn’t a tough guy. He was an ardent supporter of the MPAA, an organization that claimed children’s lives could be ruined by even a hint of unpunished homosexuality on screen. Imagining the leather-faced, steel-eyed anti-hero of The Searchers and Shane being felled by rancheros kissing is objectively hilarious.

Beyond that petty grievance (actors stay acting), the desert, or plains, or mountains themselves were never naturally deserted. As pictured by Hollywood, cowboy iconography symbolizes and endorses the past of Manifest Destiny: the idea that the formerly British, French, Dutch, now staunchly American empire had a God-given right to push West, to expand, to build, to prepare the fallible idea of a nation for civilization, as if no one was there in the first place. To reframe a cowboy’s call to nature in this way is to not only acknowledge him as a tool of mass genocide, but also as a massive tool. How can you be a lone wolf when your burden is inseparable from your tools of exploitation? Why do your aesthetics rely on continued emptiness – of land, and apparently of meaning.

But Shayna, what place does dissing cowboys have in your gay film newsletter?

Oddly enough, another type of reviled, contestable loneliness emerges when I think of the tendency to group lesbian films, and sometimes just lesbian identity, into a category of unrequited yearning. Loneliness, daydreaming, sighing, and never quite colliding for that tremulous caress has somehow become a picture of lesbian normal. But this depression is often joked about and tinged pastel; as if it’s an aesthetic goal, an acceptable way to tiptoe around desire, and a lighthearted shyness or klutziness that comes with the territory of wanting to be with another woman. It casts the possibility of acknowledged love, sex, and connection in a perverse light, as if it’s too harsh, even offensive, to the iconography of Sapphistry.

Rarely do I encounter loneliness, especially lesbian-specific loneliness, referenced the way I experience it in my own life: hard. Fucking difficult. Filled with a visually unappealing rage and bitterness. Flat out embarrassing. Scraping my insides until I don’t recognize myself or the actions that previously brought me joy. And in my most cynical moods, rarely do I see an image of a cowboy that doesn’t make me think, “that’s showbiz.” But lucky for me, the films I want to highlight for this newsletter touch the truth of that frustration, isolation, eventual catharsis, and, perhaps most importantly, cowboys.

______________________________________________________

If you’ve read any previous work of mine, you likely know how much I adore the still-underrated lesbian cowboy classic Desert Hearts (1985). In Donna Deitch’s singular portrait of a tightly-laced college professor in town for one reason and one reason only (a quickie divorce), two lonely women collide in lust, frustration, and expertly-embroidered western wear, illuminating a path forward despite the supposedly dim future of 1950s lesbian possibility.

Another time, I’ll talk about how it (along with Todd Haynes’ Carol, and Sebastián Lelio’s Disobedience) is a precursor to deceptively straightforward “big name” lesbian films that keeps getting richer every time I watch it. How it has some of the most interesting rebuttals and blurring of labels, even for its “heterosexual” characters, that I’ve ever seen. And how it’s lonely, and funny, and makes fun of its own loneliness. And that’s honesty, baby.

Deitch’s drama, so much lusher and grander than its budget would have you believe, pulls many of its awe-inspiring visual elements and archetypes from classic Western landscapes, but it treats loneliness as something created out of fear of vulnerability, not a never-ending, nobly self-fulfilling prophecy. Its lovers have to own up to what’s preventing them from connection, and their reasons by turn hold water, and dissolve in the light of confession. And it’s all accompanied by Deitch’s most hard-won creative decision: its soundtrack.

On my most recent rewatch of the film (one of my pastimes is making friends and lovers watch it with me so that I can enjoy their first-time reactions, like some sort of lesbian cinephile energy vampire), I thought about the score. I thought specifically about Patsy Cline’s “Crazy,” one of Deitch’s most expensive and dear additions, as it rolls over a montage of blues and purples highlighting the blush of attraction. And I thought about another singer of the loneliest cowboy variety, whose tortured voice has been compared to the long-extinct river carving the canyons through which Desert Hearts’ Vivian and Cay drive.

Chavela (2017) is Catherine Gund and Daresha Kyi’s character study of the iconoclastic, masculinely-attired ranchera singer Chavela Vargas. The documentary connects Vargas’ untapped emotion, unrivaled talent, and deep despair to form a portrait of a powerhouse whose demons are only truly kept at bay through her music. Together, Chavela and Desert Hearts are known as Shayna’s Angry Lesbian Cowboys (With Real Problems) Who Fuck.

-------------

Content warnings: abuse, alcoholism

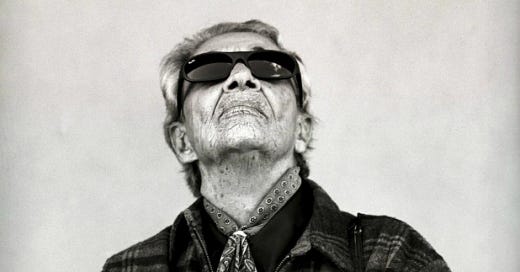

Chavela opens with 1991 interview footage between the ultra-cool, charming singer - then in her seventies - and the filmmakers. In dark glasses and a breezy blouse, she’s charismatic, challenging, and flirting with aplomb and sending “love to all the women in the world.” In another opening clip, also captured by filmmaker Catherine Gund, Vargas maintains this ultra-cool charm and control of the room as she resists a dig into her past.

“Let’s start with where I’m going, not with where I’ve been.” It’s an interesting request from a figure whose life, clearly riddled with deep pockets of sadness, travels roads utterly inconceivable by most people. For starters, Vargas emigrated from Costa Rica to Mexico when she was just seventeen, seeking more opportunities for her burgeoning voice, as well as an escape from the family that physically hid her because of her defiantly unfeminine appearance.

The documentary discards Vargas’ request at first, putting together a straightforward biography before eventually coming back around to Vargas’ contemporary life and resurgence in popularity, as well as her eventual public embrace of the word “lesbian.” It’s a wise choice – as captivating as Vargas’ more recent iteration is, the detailing of her past brings a welcome context to her famously rugged appearance, and most importantly, her singing.

Vargas’ voice digs into the marrow of sadness. She’s angry, she’s desperate, she’s hopelessly in love, and she’s lonely - but only ever on stage or in recordings. This is where her vulnerability is allowed to truly rule her outward expression, where what she presents to the world matches the internal turmoil that would reveal itself in years of tumultuous affairs and consumingly intense romantic relationships, both with women and with whiskey. She can be fiercely aggressive, or starving for the return of her erstwhile companion, but no matter what, on the stage she can unleash the truthfulness feared and scorned by her earliest caretakers.

In archival clips that range from her early appearances at El Cuid and her hideout cabarets in Mexico City, to her short but steely turn as a romantic fictional version of, well, herself in La soldadera / The Female Soldier (José Bolaños, 1967), Vargas is macho, growling, swaggering (and I would recommend this documentary just for a swooning glimpse of Vargas in La Soldadera). With her signature poncho and scandalous pre-1950s pants, Vargas eschews the crinoline, earrings, and lipstick that she was first coerced into by her family, and then by the expectations pasted onto traditional ranchera singers in the limited musical spotlight. She wields the guitar as a weapon and an invitation, grinds her teeth and exudes warmth with a knowing smile. She is so steady in the spotlight that the descriptor of “bravery” is an afterthought, and a paltry one at that. Forget John Wayne; Chavela Vargas is the cowboy, and she knows true loneliness just like she knows the promise of a lover’s embrace.

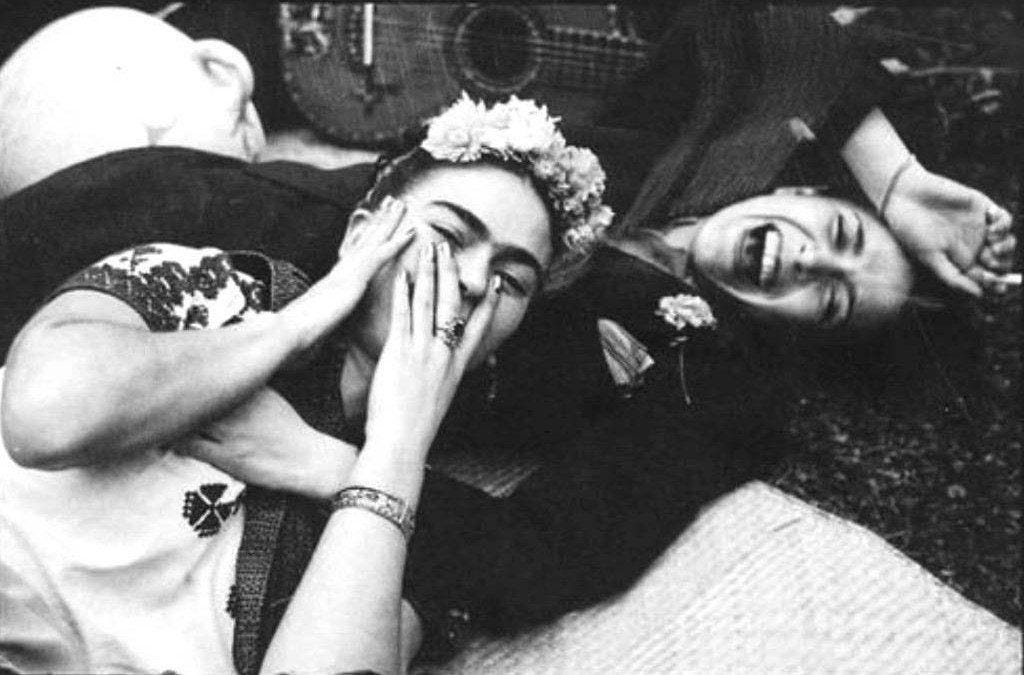

To an uninitiated listener whose first oblivious connection to Vargas was through her adoption by famed gay melodrama maestro Pedro Almodóvar (it’s me, I’m the uninitiated sap), Vargas’ alto seems propelled by inner strength alone – by a constitution that dares “butch” and “dyke” to come out and play. As many of you might know her, Vargas’ status as lover to Frida Kahlo infuses her with such badassery and legend that the toughest sharpshooter would do well to quake in his boots. But Chavela explores the overcompensation of Vargas’ persona to mask a terrible stage fright and a long-held refusal to publicly declare herself as a lesbian (even if, from a young age of sneaking out of her house to follow cantadores and gaze upon the moon, she knew exactly who she was).

To this end, as the documentary and Vargas herself explain, alcohol was her greatest support and malady. Heavy drinking was a rite of passage for rancheros, and happy weekends would pass by in the blink of an eye under the tutelage of the fervent drinkers and celebratory singers and musicians in her circle. According to Vargas’ ex-lovers and friends, working through the documentary with remembrances both fond and injured, lesbians had no previous place (at least publicly) in Mexican music, and “to become Chavela, she had to be stronger, more macha, and more drunk than any singing cowboy around.”

In one of my favorite choices from the documentary, Gund and Kyi unearth scenes from La soldadera/The Female Soldier, in which Vargas plays a gruff, handsome mentor teaching the women of the village to pick up a gun and look out for themselves. As Vargas squints and swaggers about the set, ex-partner and longtime friend Alicia Pérez Duarte expounds upon the “legend” of Chavela, the woman who dressed like a man and could sweep up any woman she wanted. Watching Vargas in La soldadera, or any other stage appearance where she plays the same character, evokes some contradictory feelings. It’s abundantly clear that she’s a dyke icon to be feared and adored, but in order to protect herself from ostracizing and that same shame of her childhood, she both fortifies and refuses to name the source of her strength. Binge drinking, a much more accepted practice than lesbianism, takes precedence.

The documentary illustrates Vargas’ self-destruction, as well as her intoxication-fueled abuse toward her ex-partners. Some give accounts of her hot and cold behavior, both before and after her alcoholism spread into physical malady and forced her into a first early retirement and hermitage. Whether the portrayal of Chavela is biased is hardly up for debate. The film may take a critical look at the singer, but it is obviously celebrating her legacy. Nonetheless, these accounts, as well as Chavela’s own rebuke of her behavior, encourage some discomfort, and an argument for the futility of hero worship.

Chavela didn’t just sound the part of a tortured soul. With a voice that “stripped all the happiness from Mexican music, and distilled it to what it really was. The music of desperation,” she was tortured, and could lash out at those who cared for her in all states of vulnerability.

________________________________________________________________

To be frank, I often find it difficult to persuade myself to engage with something honest and prodding, that threatens to make me open the spigot. Some days, I reject any honesty in art completely. I’ll watch the Western, or the fluffy candy-colored spectacle, because it’s fun! It doesn’t make me turn any sort of mirror back on myself! It’s not a light task to witness someone, especially someone who has allowed others to fully experience their emotions through her art, tell the truth about their ugliness. As skillfully as I avoid it because of its utter unpleasantness, that truth is hard-won and valuable, and embracing it allows me to recognize and respect the pain in my own life.

Chavela is a somewhat complicated rendering of a complicated person, but I can’t thank it enough for giving a spotlight to art that makes me feel. Alongside Desert Hearts, it presents the chance to evaluate a tradition of grieving what might, in all honesty, be within reach. There’s also an invitation to fully mourn, with one’s entire body, the wrongs and non-apologies of those who will never be truthful or regretful. Finally, there’s the release of he who pictures himself riding into the sunset of his own making, without a concern for those he failed to acknowledge in the first place.

You can stream Desert Hearts on the Criterion Channel (or ask to borrow my DVD).

You can stream Chavela on Tubi for free.